Blog

Sherpa solidarity–from Queens to Nepal–standing up to the legacy of the mountain

A strike? Boycott? Talk of a union?

Not exactly what you’d expect to hear from a humble Nepalese sherpa. But these days, the Sherpa wants to be seen more as an elite mountaineer and less of a lowly manservant/mule.

Indeed, if Twitter were around during Sir Edmund Hillary’s historic scaling of Mt. Everest in 1953, the most famous Sherpa ever, Tenzing Norgay, might be tweeting #NotYourAsianSidekick.

That’s why the adventurers and climbers from around the world, hoping to scale Everest this season, are turning back and coming home.

The mountain is closed.

The one-day boycott of the Sherpas this week has been extended until better conditions can be established for them.

The urgency of that was made clear April 18. That’s when the world fell, quite literally, and changed everything for the Sherpas and those who seek their services. A serac– a column of glacial ice that juts up like a pointy cathedral–tumbled half way up Mt. Everest. The act of gravity created a massive avalanche of icy rock, killing 16 Sherpas.

Many of them were friends and climbing buddies of Serap Jangu Sherpa.

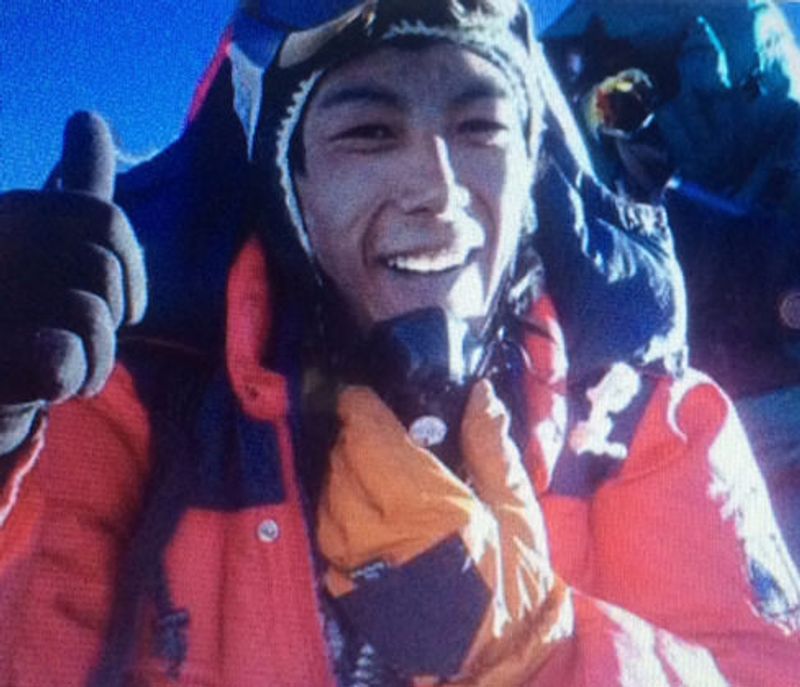

Then Dorji Sherpa, 33, pictured here with the thumbs up sign on a past expedition, was more than just related to Serap by marriage.

“He was my best friend and climbing buddy,” said Serap, 45, who now lives in New York City and works in an outdoors sporting goods store.

An elite mountaineer, Serap is president of the U.S. Nepal Climbers Association, a group of about 19 ethnic Sherpas who grew up in the rarified air of the Himalayas and for whom climbing the mountain was seen as their only way up in life.

Serap is the first person to climb K2, known as the second highest peak in the world at more than 28,000 feet. His distinction? He did it twice within 12 months.

He was also the first Nepalese to complete the circuit of all the peaks in excess of 20,000 feet in 2009.

And Everest? Of course, he’s made it to the summit. Three times.

But even then, as someone who climbed and led nearly 30 expeditions, there was no future for him in Nepal–even though it would appear there is plenty of money to go around.

Climbers from around the world come to Nepal and pay around $11,000 for one climbing license. Multiply that by 1,000 or so, and you see the millions of dollars the government takes in.

But the climbers get a miniscule fraction of that. In a climbing season, Serap said a climber can make about $5,000 for a two- to three-month period. In a rupee economy, they make it last until the next climb.

That’s why the Sherpas are meeting with the government and demanding more. Many saw it as a slap in the face when survivors of the 16 victims were offered a mere $400 in insurance money.

It only fueled the anger and upped the demand–now $20,000 in insurance and care for survivors.

Still, it’s a small price compared to what Nepal takes in from adventure tourists.

Serap, like the others in the large Sherpa community in Queens, have spent the last few weeks mourning.

They follow the news back home and are united with the Sherpas there.

In my phone conversation, I sensed Serap’s sadness. He sells equipment to adventurers now and does some indoor climbing in New York. He’s unhappy that the season is ending prematurely.

“I miss the mountain,” he says.

But then he remembers his friend, Then Gurji Sherpa, and the others lost in the avalanche, and says unequivocally, “We support the strike.”

Emil Guillermo is an independent journalist/commentator. Updates at www.amok.com. Follow Emil on Twitter, and like his Facebook page.

The views expressed in his blog do not necessarily represent AALDEF’s views or policies.

Read Emil's full bio →